This story will prove the old saying “one thing leads to another” to be true…you never know where life will take you or what kind of impact one person or event can have!

I am willing to bet you haven’t heard of William Perkin before. I hadn’t. He is the English chemist (and I don’t mean pharmacist) whose work started science-based industry as we know it today.

I promise I won’t bore you with chemistry formulas and jargon (I’m no chemist myself!), I just find his story fascinating.

A CHEMICAL ROMANCE

Believe it or not, in the 1850’s chemistry was not given much respect. Most schools didn’t teach it. There was distrust in the process—some thought it was a bunch of hocus-pocus.

Even so, young William Perkin was intrigued by chemistry.

Naturally inquisitive, at age thirteen William matriculated to the City of London School. There he found chemistry was available as an elective given during two lunch periods per week—yes, this boy gave up lunch to learn chemistry!

At fifteen Perkin went to the Royal College to study under the famous chemist August Hofmann. That was 1853. In just a few short years Perkin made his fortune, and changed the world.

A STRANGE THING HAPPENED ON THE WAY…

One way or another we have all been influenced by our teachers. Malaria was a huge problem in the 19th century. It was August Hofmann’s particular dream to find the synthetic equivalent to the only medicine that effectively treated malaria: quinine. Derived from cinchona bark, it was rather scarce.

You really didn’t want to contract malaria. Ignorance and scarcity led to the usual bad medicine of the time: blood-letting, administration of mercury…or…you could eat a spider. Or just carry one in a nutshell.

A standard cure was needed. So wanting to impress, Perkin pursued his teachers cause on his own time, focusing his research on coal-tar, a by-product of the gas industry. Think of all the gaslight in London at the time…a use for the waste would be welcomed!

One day, Perkins was cleaning up the by-product from a failed experiment, and found it stained cloth purple. It was one of those unexpected results of experimentation…and had nothing to do with a cure for malaria.

So in 1856 William Perkin discovered the first artificial color and hence, the entire chemical engineering industry was born.

I SAY MAUVE, YOU SAY MORV…

At the time, a true man of science would not be caught dead discovering new ways to make clothes pretty.

But this “stain” proved to be color-fast, not fading with washing or exposure to sun—major issues in the textile industry of the day. And generally purple was a tricky color to produce, the reason it was associated with royalty.

Initially the only way to get purple was from the mucus glands of the Murex genus of mollusks, and then a French company discovered how to get it from lichen, a product known as French Purple.

In fact, “mauve” is what the French called the color, and the English adopted the word, so Perkin’s chemical was named mauveine.

His timing was perfect. The Empress Eugenie of France had taken a liking to the extravagant color… Unlimited Budget + High Profile = Demand!

At that very time women’s magazines started hitting the stands. These magazines featured the Empress’ love of mauve (or as the English pronounced it, morv) and women wanted to emulate her…the market was ripe!

Perkin was 18 years old when he applied for a patent. By 1857 he had the kinks worked out and entered the dye market…bringing purple to the masses, and so much more!

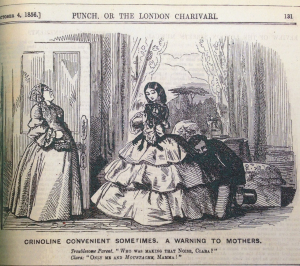

As with most fads mauve burned hot and fast. So hot that at its height “mauve mania” was dubbed Mauve Measles by the satirical mag Punch, “…Although the mind is certainly affected by the malady, it is chiefly on the body that its effects are noticeable.”

Mauve raged until 1861, in part thanks to the popular hoop skirt. Women had more acreage to show off with, and what was more showy than mauve?!

Making fun of fashion, Punch, October 4, 1856. CRINOLINE CONVENIENT SOMETIMES. A WARNING TO MOTHERS.

Troublesome Parent.”Who was making that noise, Clara?”

Clara. “Only me and Moustache, Mamma!”

Public Domain.

By the mid-1860’s mauve had transformed from a fancy, fun look to a symbol of mourning. Queen Victoria herself, who after losing her Albert spent four years in black, made the move to mauve.

By 1869 the fad was over.

THE BAD WITH THE GOOD

After several more years in the dye industry, William Perkin sold his production plant and retired at the ripe old age of thirty-five.

Perkin’s success in coal-tar derivatives impacted society both for good and bad:

- His dyes were able to stain the tuberculosis and cholera bacteria, enabling further research into treatment and prevention.

- They also made their way into the food industry particularly in candy and meat at the time (and they still are in our food).

- Further research enabled the pioneering of immunology and chemotherapy.

- There was concern and controversy over toxins leaching out of fabrics especially when dampened by rain or sweat. The shah of Persia forbid the import of these dyes as he did not want to risk the reputation of Persian rugs.

Testament to the profound impact William Perkin had is the annual bestowing of the Perkin Medal, the highest honor given in the U.S. chemical industry. He was the first recipient on the fiftieth anniversary of the discovery of mauveine in 1906. The men who attended the ceremonial banquet all wore mauve ties.

Perkin learned later in life that his grandfather had been an alchemist. The goal of alchemy is to turn base material into gold…something William actually managed to do by following his passion!

I know I’ll never look at purple clothes the same way! What about you? Do you have a similar story of a surprise turn of events in your own life? Tell us in the comments!

SOURCES:

Garfield, Simon. 2000. Mauve: How One Man Invented a Color That Changed the World. New York, NY. W. W. Norton & Company.

Perkin, W. H. On Mauve or Aniline-Purple. Proceedings of the Royal Society of London, Vol. 13 (1863-1864): 170-176.

Travis, Anthony S. Perkin’s Mauve: Ancestor of the Organic Chemical Industry. Technology and Culture, Vol. 31 No. 1 (January 1990): 51-82.

Leave a Reply